The Psychology Behind the Primacy Effect

First Come, Best Remembered: The Psychology Behind the Primacy Effect

Think about the last list of grocery items you tried to memorize.

Chances are, you remember the first few things you wrote down more clearly than the rest.

Now think about meeting someone new for the first time. Within seconds, you've already decided whether you like them, trust them, or not and that first impression tends to stick, even if you later learn something that should change your mind.

These small, familiar moments reveal something powerful about how our minds work: we give special weight to what comes first.

Psychologists call this the Primacy Effect, which they explain as our tendency to remember and favor early information over everything that follows.

From studying for exams and sitting through job interviews to how companies market their brands, the Primacy Effect quietly shapes what we remember, who we trust, and the decisions we make every day.

What is the Primacy Effect?

The Primacy Effect is a psychological phenomenon that explains why the first information we encounter tends to stick in our minds the longest.

In simple terms, it means "first come, best remembered."

When we're exposed to a list of words, facts, or even traits, we naturally give more attention to the first ones and as a result, they're stored more effectively in memory.

The effect was first explored by psychologist Solomon Asch in 1946. In his classic study, participants were given two descriptions of a person using the same six traits: intelligent, industrious, impulsive, critical, stubborn, envious; and the same list reversed.

The only difference was the order. Those who saw the positive traits first viewed the person more favorably than those who saw the negative traits first. The first information they received shaped how they interpreted everything else.

Cognitive scientists later connected this to how memory works. When something is presented first, we tend to rehearse it more; repeating it mentally, making it more likely to move into long-term memory.

Later information, by contrast, competes for attention and often fades faster.

In other words, what we learn or perceive first doesn't just come before everything else: it colors how we understand the rest.

How the Primacy Effect Shapes Memory and Learning

You've probably experienced the Primacy Effect without realizing it!

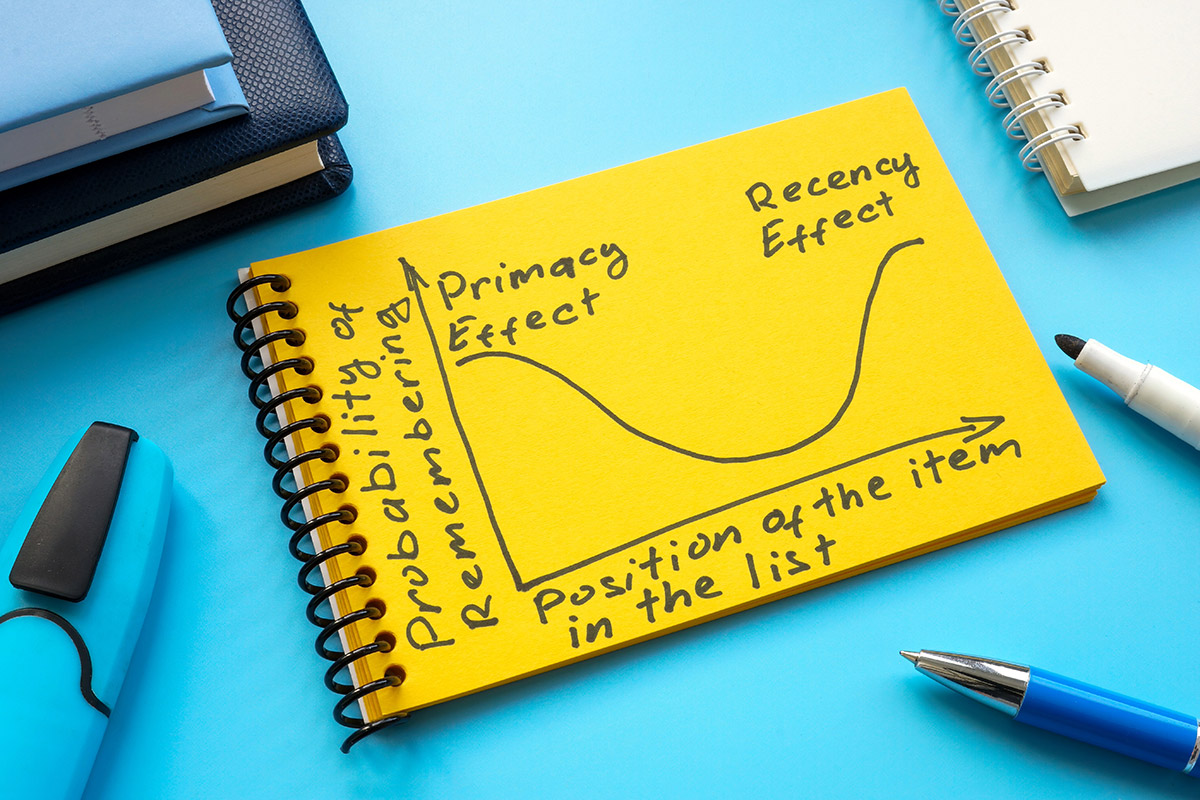

Think about when you're studying or trying to memorize something. Imagine reading through a list of twenty words. When asked to recall them later, most people remember the first few and the last few, while the middle items vanish from memory.

This pattern is known as the serial position effect, and the Primacy Effect makes up the "first half" of it.

That's because early information gets the most attention. When we first start learning, our minds are fresh and focused. We also tend to rehearse those first items mentally, giving them extra time to move into long-term storage. As new information piles up, our attention and memory resources get stretched thinner, making the middle content more likely to fade.

Teachers and learners can use this to their advantage. Start lessons or study sessions with the most important or difficult topics, since they're the most likely to be remembered.

Short breaks or topic transitions can also "reset" attention, helping new information feel like a fresh beginning and effectively creating multiple "firsts" in one session.

First Impressions and Decision-Making

The Primacy Effect doesn't just shape what we remember: it also shapes what we believe.

The first information we receive about a person, product, or idea tends to anchor our judgment, coloring how we interpret everything that comes next.

This is especially true when it comes to first impressions. Within seconds of meeting someone, we've already formed an opinion, whether we realize it or not. If someone greets us warmly, we're likely to overlook their later awkwardness.

If they seem cold at first, even a friendly gesture later might not fully change our mind. Psychologists call this "impression anchoring": once that first mental picture forms, it takes effort to redraw it.

The same happens in decision-making:

- In job interviews, for example, interviewers often form early judgments in the first few minutes, which subtly influence how they interpret later answers. In marketing, brands rely on the same principle.

- The first advertisement or interaction we have with a product can define how we perceive it long-term — which is why companies invest so heavily in first impressions, from packaging design to website layout.

Even in everyday choices; like choosing a restaurant, evaluating news stories, or meeting someone on a first date. Our brains are wired to trust early cues.

We like to think we weigh all the evidence, but often, the first thing we see quietly sets the tone for everything else.

Can We Overcome the Primacy Effect?

This may be a natural part of how our brains work, but that doesn't make us powerless against it.

In fact, simply being aware of it is the first step toward using it wisely or neutralizing its influence when it leads us astray.

When forming opinions about people, for instance, we can try to pause before judging. By waiting to gather more information, or by reminding ourselves that first impressions can be misleading, we give later details a fairer chance to register.

In communication, the Primacy Effect can actually be an ally.

Leading with your strongest points — whether in a presentation, an argument, or a job pitch — helps ensure that what you say first is what people remember most. That's why great speakers and storytellers spend extra time perfecting their opening lines: they know that attention and memory are sharpest at the start.

And for students or lifelong learners, the key is structured repetition.

Review middle or later material more often to offset the natural bias toward what was learned first. Small adjustments, like studying in shorter blocks or reshuffling topics between sessions, can make a surprising difference in long-term retention.

The Primacy Effect is powerful, but it's not destiny. With a little awareness and intentional structure, we can make sure that "what comes first" doesn't always have the final word.

Why First Still Matters

In a world overflowing with information, firsts still hold a special kind of power.

The first thing we learn, the first person we meet, the first story we hear — each one leaves a trace that's hard to erase. The Primacy Effect reminds us that our minds are not blank slates, but pattern-seekers that anchor meaning to whatever comes first.

This can be both a gift and a trap.

It helps us make quick sense of the world, but it can also blind us to new perspectives. The key is awareness: to value first impressions without letting them harden into final judgments, and to structure our learning and communication so that what comes first works for us, not against us.

Because in memory, marketing, and even in life; firsts may not always be best, but they're almost always remembered.

SEARCH ARTICLES

advanced search tips examples: "Yoga Meditation" Therap* +Yoga +MeditationRecent Posts

Nov 27 2025

The Psychology Behind the Primacy Effect

Jun 24 2025

Microplastic Exposure: Bottled Water vs Tap

Jun 09 2025

Squats for aligning hips

Apr 29 2025

Creative Thinking

Jan 28 2025

How to talk to someone you disagree with

Jan 27 2025

Alcohol Causes Cancer

Jan 14 2025

The role of the Amygdala

Oct 04 2024

A Support Guide for Anorexia Nervosa

Jun 25 2024

Sleep better